I write novels for a living, and novels are about how characters deal with the intrinsic conflicts that make them who they are — and their efforts to overcome them. Sometimes characters are able to overcome their conflicts and sometimes, in tragedies, they succumb to them, which results in ruin. This is why it troubled me so much to witness recent events unfold like something out of a book.

Part of the heartbreak of watching the nightmare up the highway from me in Dallas was seeing, like a story's dramatic conclusion, several of America's greatest inherent conflicts coming together in one moment: fatally disastrous policing; our unresolved racial legacy dating back to the original sin of slavery and the century of socio-economic disenfranchisement that followed it; our love of guns and our reoccurring shame of the mass murders made possible by them.

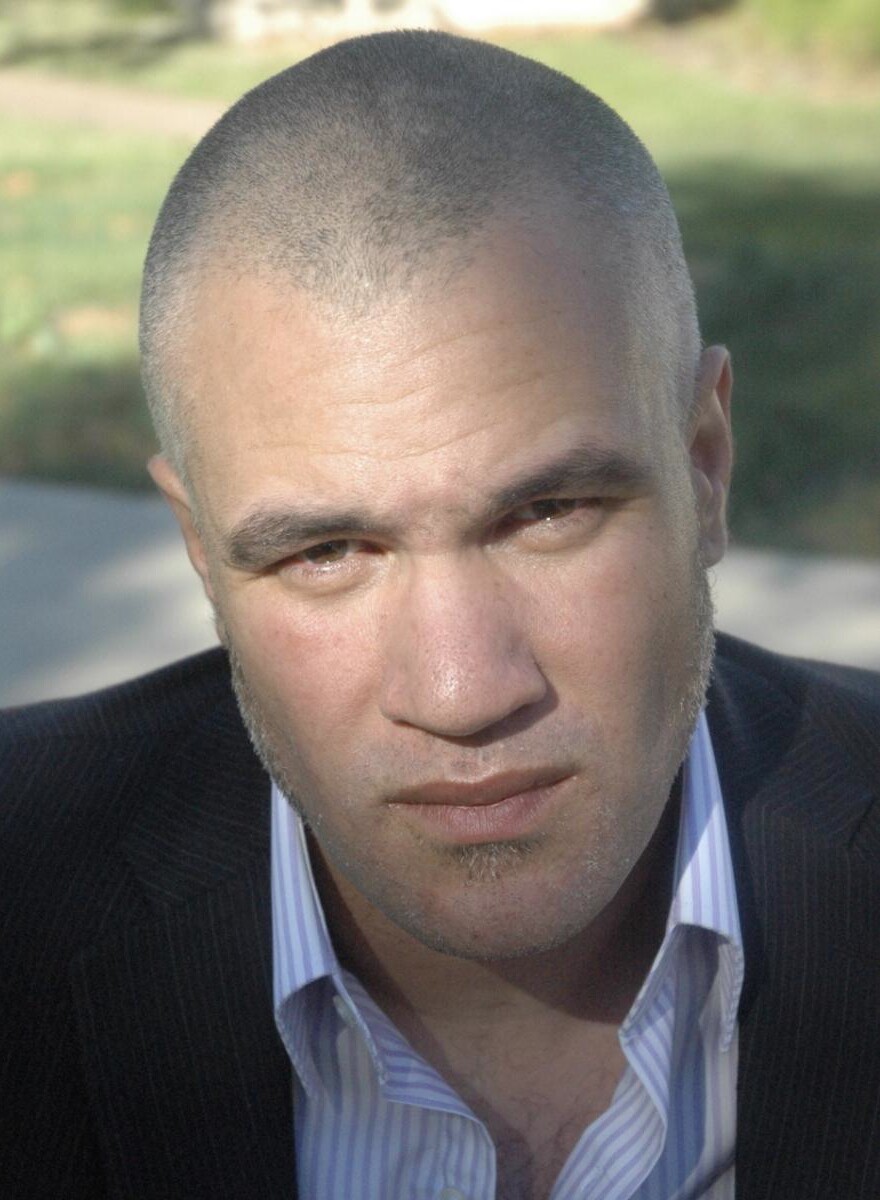

I watched that night in Dallas, like everyone else, through the lens of my own backstory: When I saw Philando Castile in Minnesota lying shot in his car, I thought of the time I was pulled over for "speeding" while stopped at a traffic light in East Houston, or when I was pulled over for making a right-on-red in Giuliani's New York. That time, the cop and I both knew that the light had been green; the stop was just an excuse to run my info through the system because he didn't like the way I looked.

When I saw Philando Castile in Minnesota lying shot in his car, I thought of the time I was pulled over for "speeding" while stopped at a traffic light in East Houston.

I thought of what might have happened in those moments if I wasn't privileged enough to pop into my most professorial voice, flash a faculty ID and access all the adjacent off-white privilege my mixed heritage could provide.

I watched Dallas, as officers in a police force commended for their de-escalation efforts were murdered in the streets, and thought about teaching at my public university in Texas, where students this fall will now be able to legally walk through campus strapped with AR-15s on their way to pick up their grades.

And I know others watched the events in Dallas, and watched the unraveling in Baton Rouge, with their own personalized scenes in their head, their own back stories, their own choice of media-catered facts, their own inherited prejudices, and came to completely different truths about what is going on in the world right now.

When I was growing up, my mother taught me two central things about dealing with the cops while black, the same principles many black parents taught: First, that if you just stay out of trouble and docilely comply with whatever the cops want, you'll be OK; and second, that if the rest of the world saw what was really happening in deadly interactions between black people and the police, they'd see the problem.

At this moment, those ideas seem like wishful self-delusions. I don't know what to tell my kids.

A short while before his life was stolen, slain Baton Rouge Police Officer Montrell Jackson posted a Facebook message that was eerily prescient of the national moment that would soon claim his life. He wrote, "In uniform, I get nasty hateful looks, and out of uniform some consider me a threat." His ultimate conclusion — "These are trying times. Please don't let hate infect your heart" — showed the type of insight that made him exactly the type of officer we need out there. Now he is lost to us.

Right now, in the streets, online and on TV, we as Americans are fighting over control of the national narrative: Are these acts of violence the fault of the protesters, the police or a larger criminal-justice system that's failing everyone?

I understand why those who feel they aren't directly affected by this issue would be tempted to react to the complexity of what's going on by scapegoating or dismissing recent events as isolated incidents. We all have full, demanding lives. No one wants to add to the burden of dramatically changing how our society is functioning to their daily duties.

But I don't have that privilege. What I have is black children. Every time a black person ends up dead after a police interaction, I read the details. I study them. I look for something they did, something they didn't do, something that I can tell my kids to avoid so that if they're ever pulled aside for a minor infraction by the wrong cop, they can come out alive.

But for every single piece of advice I can give them, there is a hashtagged name of someone who did the exact same thing — and died. I'm petrified for my children. I'm petrified for my friends' children. I'm worried about the good cops out there whose jobs are getting more dangerous because of the injustices perpetrated by others. I'm scared for our country. I fear that if we don't resolve our intrinsic conflicts — our inherent national flaws — that our story will end in ruin.

Copyright 2021 Fresh Air. To see more, visit Fresh Air.