Oklahoma again could see a push to open a religious charter school, with a Florida-based Jewish organization expressing intent to apply for state authorization.

If approved, Ben Gamla Jewish Charter School would operate as an online-based virtual charter school teaching Jewish religious studies and Oklahoma academic standards.

A previous attempt to open a publicly funded Catholic charter school in the state failed before the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this year. A deadlocked vote upheld the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s ruling against St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School.

Leading the latest effort is the National Ben Gamla Jewish Charter School Foundation, which has opened six non-religious Hebrew-English charter schools in Florida.

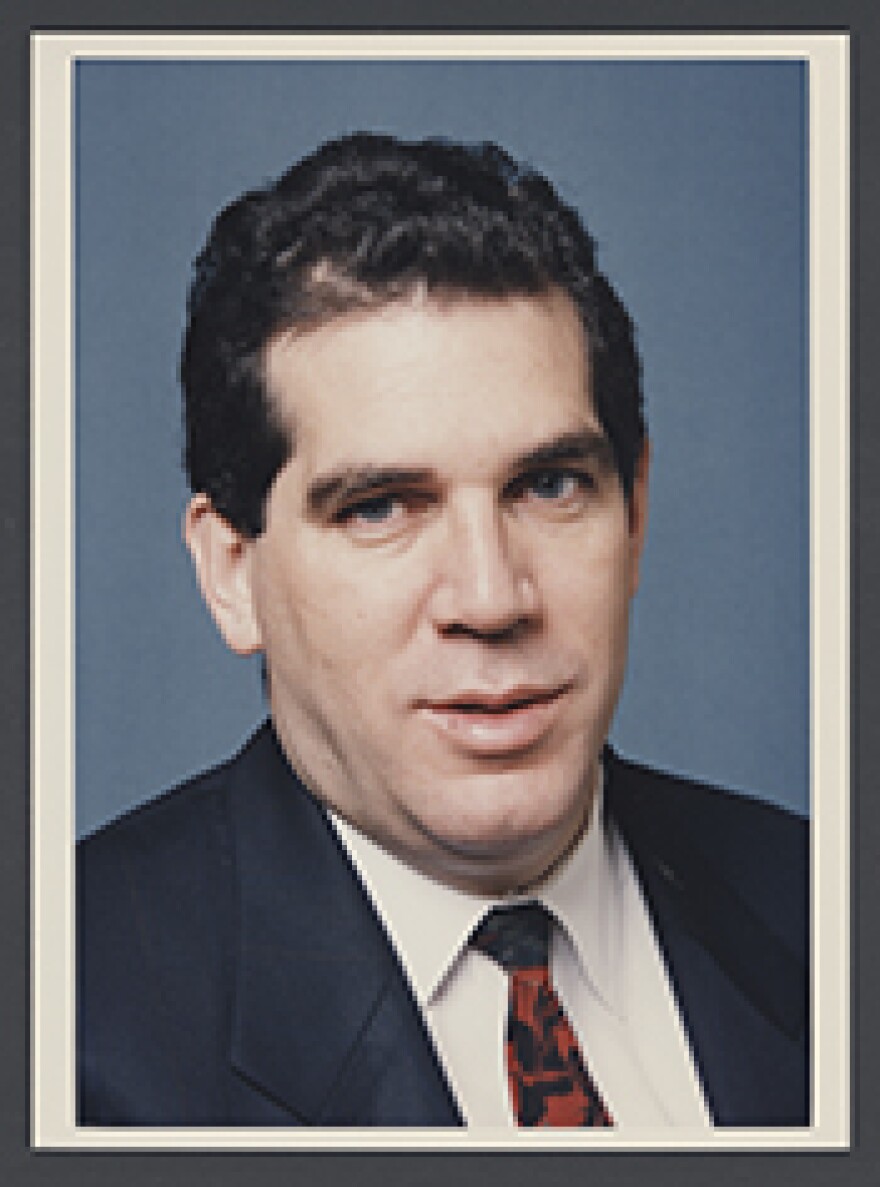

Peter Deutsch, a former Democratic U.S. representative and the founder of Ben Gamla schools, submitted a letter of intent on Nov. 3 to apply for charter authorization with the Oklahoma Statewide Charter School Board. A formal application has not yet been submitted for the school, and the board cannot take a vote until that happens.

“Ben Gamla envisions Oklahoma students gaining a rigorous, values-based education that integrates general academic excellence with Jewish religious learning and ethical development,” Deutsch wrote.

The Statewide Charter School Board backed local Catholic leaders’ attempt to open a religious, taxpayer-funded school. In 2023, a previous version of the board, which at the time focused solely on virtual charter schools, cast the landmark vote to approve St. Isidore’s founding application. The school quickly became entangled in multiple lawsuits and never opened its doors.

The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa have ended their pursuit of charter-school funding and are now opening a private online school called St. Carlo Acutis Classical Academy.

Brett Farley, a member of St. Isidore’s board of directors, is listed in Deutsch’s letter as part of the Oklahoma Jewish school’s founding team. He declined to comment Monday.

The school’s founders are aiming to open with 40 students by the 2026-27 academic year, according to Deutsch’s letter. The state board, though, typically requires at least 18 months of preparation between the date a charter’s application was submitted and its first day of school.

Board chairperson Brian Shellem said he hasn’t yet read Deutsch’s letter of intent, but he didn’t dismiss the idea of another religious charter applicant.

“We’re going to consider their application,” Shellem said. “I think we need to give everyone an unbiased approach. Before we look at their (letter of intent), before we look at their application, I’m not going to prejudge something. I haven’t seen it.”

The Catholic charter school had staunch support from Gov. Kevin Stitt and other state leaders, who said it would expand quality education options for Oklahoma families. St. Isidore would have been the first charter school in the nation to advocate for a particular religion while relying chiefly on taxpayer funds.

Attorney General Gentner Drummond led the legal fight against the school, contending it would “eviscerate” constitutional church-state separation.

“This matter has already been resolved after the state Supreme Court’s ruling to prevent taxpayer funded religious charter schools was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court earlier this year,” Leslie Berger, a spokesperson for the attorney general, said Monday. “Our office will oppose any attempts to undermine the rule of law.”

Including the Ben Gamla school, the Statewide Charter School Board received eight letters of intent from potential applicants this year, an unusually high number that executive director Rebecca Wilkinson said is an “anomaly.” None but the Jewish school indicated they would adopt a religion.

Two applications have already been submitted — one from Southwest Academy Charter School and another from Tempo Montessori Charter School.

The board has 90 days after receiving an application to consider it. Shellem said votes on Southwest Academy and Tempo Montessori are “more than likely not” happening until 2026.

Moore Public Schools has already rejected Southwest Academy’s application to open with a classical-education-inspired curriculum. That rejection is a necessary step before a brick-and-mortar charter can apply at the state level. Virtual charter schools can apply directly to the state board.

Southwest Academy’s board president, Angie Ritter, said the school’s projected enrollment is 160 students in pre-K through second grade starting in August 2027. The founders are in lease negotiations with Regency Park Baptist Church for a school location, she said.

The charter academy would create another option for Moore parents who are priced out of private education and are unable to homeschool, Ritter said in a presentation to the state board.

“We believe that we can meet this need head-on by removing all of the financial barriers that would be there for parents and give them a high-quality option that’s tuition free,” she said.

Tempo Montessori would operate within the district boundaries of Union Public Schools in Tulsa. Union’s school board rejected its charter application on Oct. 20.

Tempo’s founding executive director Diane Beckham established the state’s first public Montessori school at Emerson Elementary in Tulsa Public Schools. She and TPS later opened two more programs within the district with the hands-on, student-led style of Montessori instruction.

Opening a charter school would grant greater flexibility than operating as part of a school district, Beckham told the Statewide Charter School Board in a presentation Monday.

Every child learns at his or her own pace, she said, hence the name Tempo.

The school is preparing to operate out of Destiny Church in Broken Arrow with a year-round calendar, featuring no breaks longer than four weeks. Beckham projected a year-one enrollment of 150 students in pre-K, kindergarten and sixth grade.