While state leaders, the business community and political candidates intensify their focus on improving Oklahoma public education, complaints have grown among teachers that they should have a more prominent role in those policy discussions.

“I’ve been begging people for years, for years, to ask actual teachers, ‘What do you need? What do you think would make these improvements?’” longtime Oklahoma public school teacher Jami Cole said. “We know what would do it, but we’re never asked. We’re just passed over for people who have more influence and power than what we have.”

Education, particularly reading proficiency, is primed to be a top legislative issue over the coming year, with the Oklahoma State Chamber and new state Superintendent Lindel Fields already suggesting policy changes. Student literacy has emerged as a priority issue in the 2026 governor’s race, as well.

Two weeks ago, the State Chamber announced a platform of literacy-focused policies that would have struggling readers repeat a grade. Fields, who said improving reading levels is among his top priorities, floated the idea of adding days to Oklahoma’s minimum school year length, which currently sits at 181 days or 1,086 hours.

Both ideas have generated debate and opposition from educators, particularly among the 64,000-member Oklahoma Edvocates Facebook group, which Cole administers. Educators in the group have contended the suggestion of grade repetition and a longer school year are a sign that teachers aren’t consulted often enough in education policy conversations.

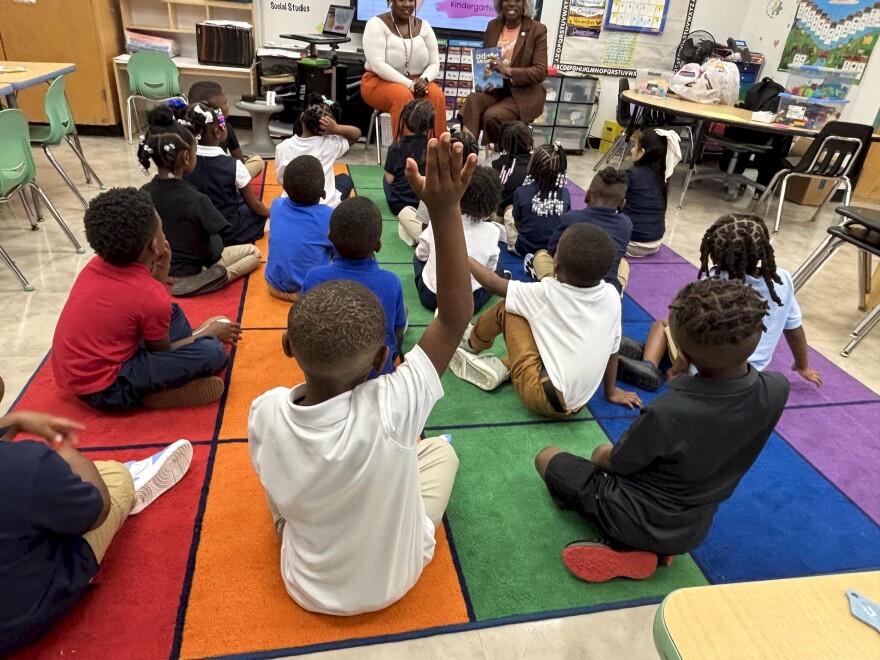

Cole said she opposes both ideas and sees a different set of needs from within her second-grade classroom. She has 23 students of widely varying education levels, she said, ranging from advanced to bordering on needing special education services.

More teaching aides, tutors and reading interventionists paired with smaller class sizes and properly trained teachers “is where the focus has to be” for state policymakers, Cole said.

“There’s so much going on in my classroom right now that I just have such a hard time with someone who has never been in the realm of teaching or education saying, ‘Oh, we just need to do this,’” she said.

The State Chamber’s plan, known as “Oklahoma Competes,” proposes a greater investment in reading coaches to assist teachers and more training in the phonics-based science of reading, along with retaining struggling readers.

The chamber announced its education plan at its State of Business Forum with endorsements from business leaders and Republican lawmakers, but not educators.

However, when developing “Oklahoma Competes,” the chamber sought input from classroom teachers, reading specialists, literacy coaches, superintendents, higher-education experts and school leaders across the state, President and CEO Chad Warmington said in a statement.

He said the chamber’s role is “not to dictate classroom practice, but to support the people who do this work every day.”

“Teachers are the frontline of this effort, and any meaningful policy solution has to reflect their experience and earn their buy-in,” Warmington said.

However, teachers still “don’t feel like they’re being heard,” said Tori Luster Pennington, president of the Oklahoma City American Federation of Teachers union, which collectively bargains on behalf of teachers in Oklahoma City Public Schools.

More interest from different groups, like the chamber, in improving education is a positive thing, she said. But her union members, who see the day-to-day realities within public schools, have given a very different list of solutions.

They cited a need for more support for students’ mental and behavioral health, she said. Chronic absenteeism also remains a persistent issue.

“Since COVID, even though we’re not in that same time, there’s still so many lingering effects of kids just not being ready and just not having the support that they need,” Pennington said. “So, we really just need more support and more engagement and helping those issues and those behaviors, and we really have to start there before we can add (school) days.”

Fields said his remarks on lengthening the school year weren’t a formal proposal, but rather a “very preliminary discussion” made during a TV interview. He said he had little dialogue with educators about the idea before floating it.

But, he’s since invited teachers to complete an educator survey to share their thoughts on a longer school year and to contribute other ideas for improving academic outcomes. The survey received nearly 4,000 responses after a week, Fields wrote in a Nov. 24 letter to teachers.

Fields said he intends to follow that up with visits to schools, education groups and teacher meetings with the goal of having open communication with teachers as he leads the Oklahoma State Department of Education.

Former state Superintendent Ryan Walters’ combative and polarizing brand of politics frayed the relationship between the agency and many educators. After Walters resigned on Sept. 30 to lead an anti-teacher-union nonprofit, Fields, a longtime CareerTech center leader, came in with a different approach, one focused on repairing those ties.

“I want to visit with teachers, hear from teachers, hear their hearts and what’s on their minds,” he told reporters after an Oklahoma State Board of Education meeting Nov. 20.

State leaders should consult teachers or risk losing valuable feedback, said Rep. John Waldron, D-Tulsa.

Waldron is a former public high school teacher elected to office amid a groundswell of support for public education in 2018.

“If teachers aren’t part of the discussion, you’re not going to get to hear from teachers who have seen what a third-grade retention test does to 8 year olds,” he said. “And if you talk about adding 15 days to the school year at a time when teacher burnout is at historic highs, then yeah, you’re not going to develop a policy that makes more people want to be teachers or stay teachers.”